What is the mirror test, and which animals pass or fail it? (Quick Answer):

The mirror test is a scientific method used to see if an animal can recognize its own reflection, which suggests a level of self-awareness. To pass, an animal must notice and investigate a mark on its body that is only visible in the mirror. While great apes, dolphins, and elephants have passed, many animals, including cats and dogs, typically fail. They often react to their reflection as if it were another animal, likely because they rely more on scent than sight for identification.

Have you ever caught your reflection in a shop window and, for a fleeting moment, not recognized yourself? That brief jolt of confusion is a reminder of a complex cognitive ability we often take for granted: self-recognition. It’s a cornerstone of what we consider to be consciousness. For decades, scientists have ventured into the minds of animals to see if they share this trait, using a simple but profound experiment known as the mirror test. This deep dive will explore the fascinating world of animal self-awareness, examining which species pass the test, which ones don’t, and what it all means for our understanding of animal cognition and our ethical responsibilities toward them.

What Is the Mirror Test? A Window into the Animal Mind

The mirror test, formally known as the mark test or mirror self-recognition test (MSR), is a behavioral experiment designed to determine whether an animal possesses the ability of visual self-recognition. It was pioneered by psychologist Gordon Gallup Jr. in 1970, and it has since become a benchmark for assessing self-awareness in animals. The premise is elegant: if an animal can understand that a reflection is an image of itself, it may possess a sense of self—an “I” that is distinct from others and the surrounding world.

The significance of this test extends far beyond simple curiosity. The discovery of self-awareness in animals has profound implications, challenging long-held beliefs about human uniqueness and forcing a re-evaluation of animal intelligence and consciousness. It fuels critical debates on how we should treat other species, influencing everything from conservation policies to the ethics of keeping animals in captivity. Understanding which creatures might share this cognitive trait pushes us to reconsider our relationship with the entire non-human world.

The Origins of the Mirror Self-Recognition Test

The idea was born from an observation of chimpanzees. Gallup noticed that after initial social displays toward their reflections (treating them as other chimps), the animals’ behavior changed. They began using the mirror to groom themselves, pick food from their teeth, and make faces—actions that suggested they knew they were looking at themselves. To test this hypothesis empirically, he devised the mark test. This experiment provided a quantifiable method to move from anecdotal observation to scientific evidence, creating a standard that has been applied across the animal kingdom for over half a century.

How Exactly Does the Mirror Test Work?

The procedure for the mirror test is methodical and revealing, designed to distinguish learned behavior from genuine self-recognition. It unfolds in several distinct phases.

Phase 1: Acclimation

An animal is first exposed to a mirror in its enclosure. During this period, researchers observe its spontaneous reactions. Almost universally, animals initially react as if their reflection is another individual. This can manifest as social behavior (friendly gestures), aggression (threat displays), or fear (avoidance). This phase is critical, as it establishes a baseline for how the animal perceives the reflection before understanding its true nature.

Phase 2: Exploratory Behavior

For species that may possess MSR, the initial social behavior subsides over time. The animal stops treating the reflection as a stranger and may begin to use it as a tool. This can involve peering around the mirror, moving back and forth to observe how the reflection responds, and exploring parts of its own body that are otherwise unseen. This shift from social response to contingency testing is a key indicator that the animal is learning the properties of the mirror.

Phase 3: The Mark Test

This is the definitive phase of the experiment. The animal is briefly anesthetized or distracted, and a researcher places an odorless, non-irritating mark on a part of its body that it cannot see directly—typically the forehead, an ear, or the shoulder. Once the animal is active again, the mirror is reintroduced.

Phase 4: Observation and Analysis

Researchers meticulously document the animal’s behavior. If the animal sees the mark in the mirror and then spontaneously touches or investigates the mark on its own body, it is considered to have passed the test. A simple touch, a rub, or a concerted effort to remove the mark all count as positive results. This action demonstrates a direct cognitive link: the animal understands that the mark seen in the reflection corresponds to a physical sensation or object on its own body. This crucial step separates self-recognition from simply reacting to a dot seen in the environment.

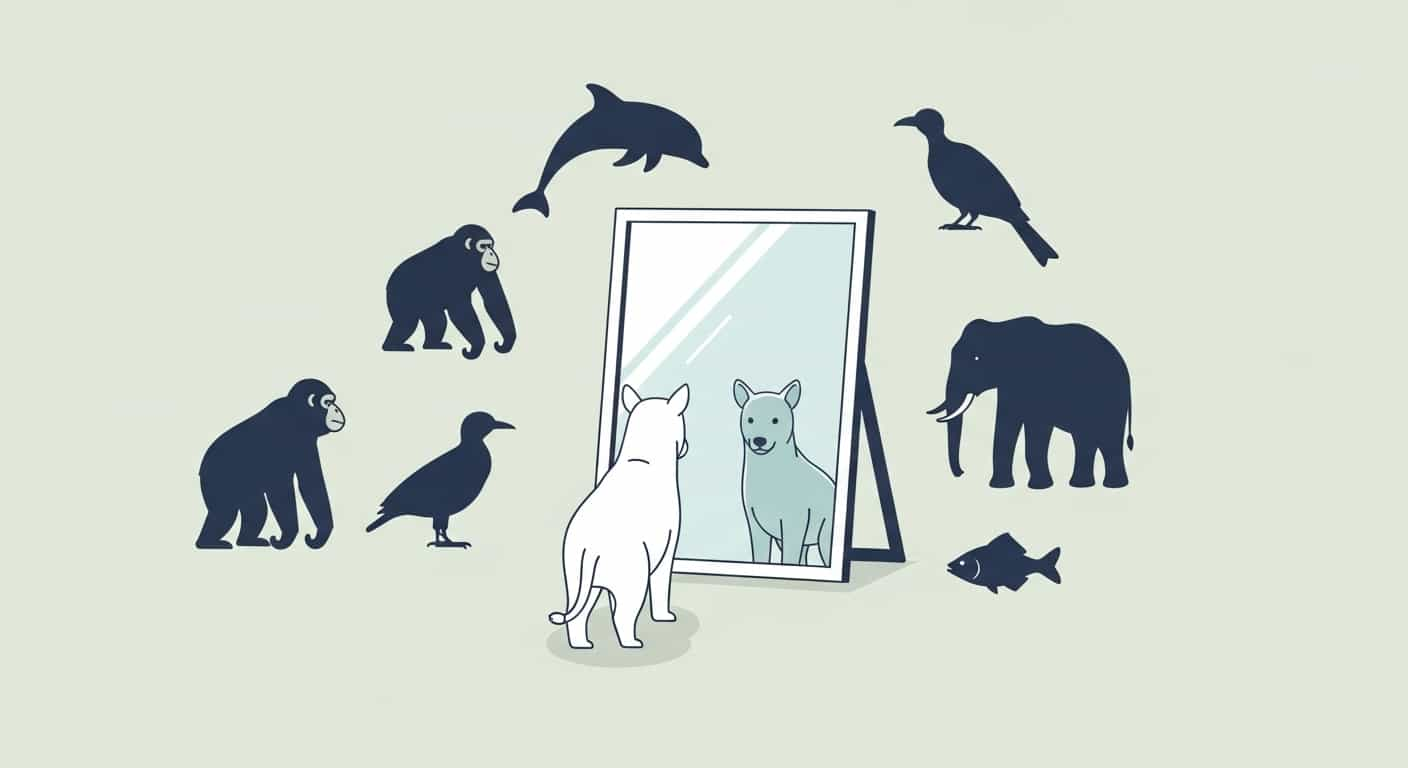

The Exclusive Club: Animals That Pass the Mirror Test

Passing the mirror self-recognition test is an incredibly rare feat in the animal kingdom. The list of animals that pass the mirror test is short, making each one a subject of intense scientific study and wonder. This exclusivity highlights how specialized this form of cognitive ability might be.

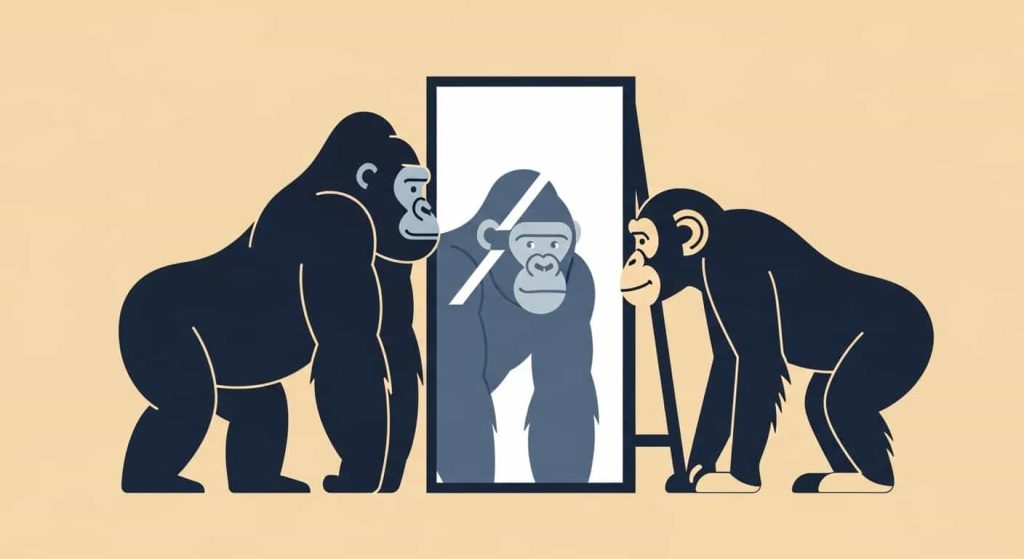

The Great Apes: Our Closest Relatives

The first and most famous members of the mirror self-recognition club are the great apes.

- Chimpanzees: Gallup’s original 1970 experiments with chimpanzees were the groundbreaking first demonstration. They reliably used mirrors to investigate the marks on their foreheads and ears.

- Orangutans: These solitary apes have also shown robust evidence of MSR, often spending long periods interacting with their reflections in sophisticated ways.

- Bonobos: Known for their complex social structures, bonobos also pass the test, further solidifying self-recognition among the Pan genus.

- Gorillas: The case of gorillas is more complex. Initially, they were thought to fail the test, which puzzled scientists. However, later studies suggested that direct eye contact is a threat signal for gorillas, so they may avoid looking at their reflection. When tested in more comfortable, non-threatening environments, some individuals, like the famous Koko, have passed the test. This highlights how experimental design can influence outcomes.

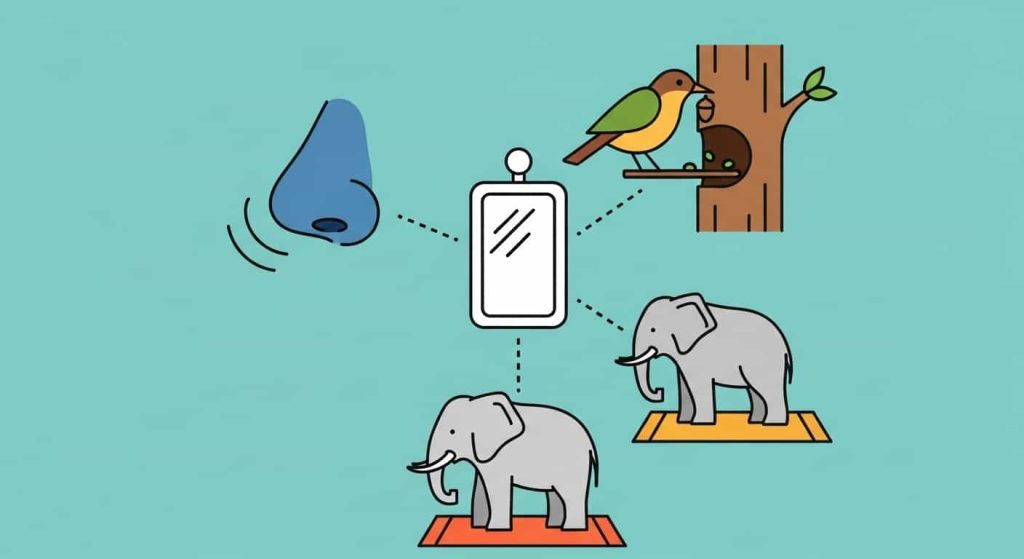

Dolphin Self-Recognition: Intelligence in the Ocean

Moving from land to sea, bottlenose dolphins provide some of the most compelling evidence of mirror self-recognition in a non-primate. In studies, dolphins exposed to mirrors quickly moved beyond treating their reflection as another dolphin. They were observed twisting and turning their bodies to see the marks placed on them. Furthermore, they used mirrors for other self-directed behaviors, like examining the inside of their mouths or watching themselves blow bubble rings, indicating a sophisticated level of body awareness and curiosity.

Elephant Mirror Self-Awareness: Gentle Giants with Complex Minds

Asian elephants joined this elite group in a 2006 study. Researchers presented elephants with an enormous 8-by-8-foot mirror. After initial investigations, an elephant named Happy repeatedly touched a white ‘X’ painted above her eye with the tip of her trunk while looking in the mirror. She did not touch a similar “sham” mark on the other side that was only visible to onlookers, proving she was specifically investigating the mark she could see in her reflection. This demonstrated not only elephant mirror self-awareness but also the need to adapt test protocols (like mirror size) to the species being studied.

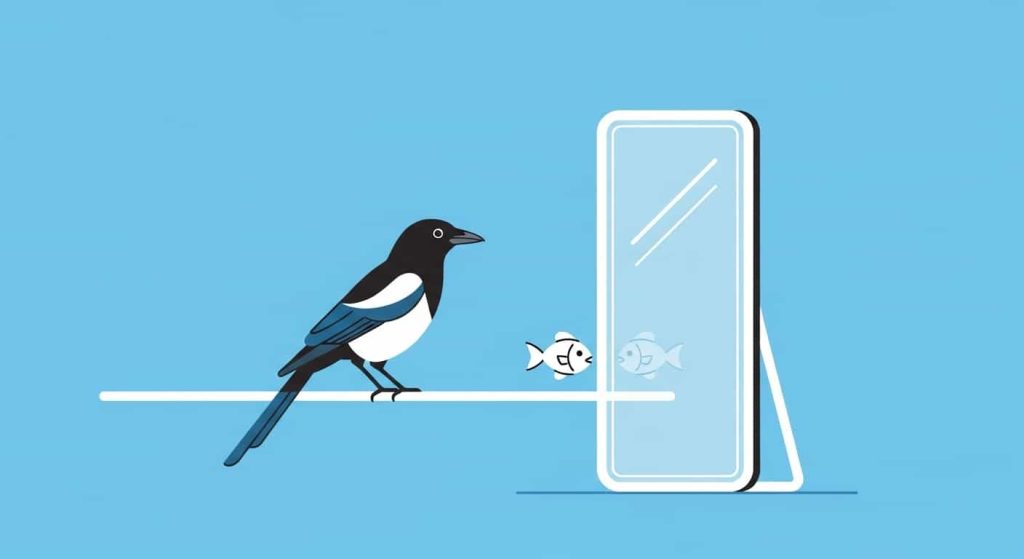

Surprising Successes: Bird Mirror Self-Recognition and Beyond

For a long time, it was assumed that only large-brained mammals could pass the test. This idea was shattered by a few surprising candidates.

- Eurasian Magpies: In 2008, a study showed that Eurasian magpies could pass the mark test. When a small yellow sticker was placed on their black throat feathers, the magpies used the mirror to locate and try to scratch it off. This was a landmark finding, as the bird brain is structured very differently from a mammalian brain, suggesting that self-awareness can evolve through different neurological pathways.

- Cleaner Wrasse: Perhaps the most astonishing success story is that of the cleaner wrasse mirror test. In a 2019 study, scientists placed a brown mark on the fish’s throat to resemble a parasite. The fish, after seeing the mark in the mirror, proceeded to scrape that part of their body against rocks to remove it. This result sparked intense debate and mirror test controversy in animal studies, with some critics arguing the behavior could be explained by simpler mechanisms. However, the study’s authors conducted numerous control experiments to support their claim, challenging our very definition of where intelligence and self-recognition can arise.

How many animals can recognize themselves in a mirror test? To date, the confirmed list is very short, including only a handful of great apes, dolphins, elephants, and a couple of bird and fish species. This rarity makes the question of why so many other intelligent animals fail just as compelling.

Why Do Most Animals Fail the Mirror Test?

The list of animals that do not pass the mirror test is far longer than the list of those that do. This includes many highly intelligent and social animals, including two of our most beloved companions: cats and dogs. Their failure, however, does not necessarily mean they lack intelligence or self-awareness; rather, it highlights the limitations of a purely visual test.

Do Cats Pass the Mirror Test? The Feline Fascination

If you’ve ever watched a cat encounter a mirror, you’ve likely seen the classic reaction: cautious curiosity, followed by swatting, hissing, or looking behind the mirror for the “other cat.” Eventually, most adult cats learn to ignore their reflection. So, why can’t cats recognize themselves in the mirror? The answer lies in their sensory world.

Cats are profoundly olfactory creatures; their sense of smell is their primary tool for identification. A reflection looks like a cat and moves like a cat, but it crucially lacks a corresponding scent. This sensory mismatch creates a puzzle that the cat cannot solve. The image is an imposter—a visual ghost without a physical, scent-based identity. While you might hear anecdotal claims like “my cat recognizes himself in the mirror,” these are likely misinterpretations of the cat simply becoming habituated to the strange, scentless “cat” that mimics its every move. The same applies to still images; there’s no evidence that cats can recognize themselves in a picture or that they can identify their own reflection.

The Dog Mirror Test: A Question of Scent

Similarly, the dog mirror test almost always ends in what is considered failure. Dogs may bark at their reflection, try to initiate play, or quickly lose interest. Like cats, dogs navigate a world dominated by scent. Their noses are exponentially more powerful than ours, and they use unique scent profiles to identify themselves, other dogs, and humans. A reflection is visually a dog, but it is olfactorily a void. This lack of scent information prevents them from making the connection that the image is them.

So, are dogs self-aware? Many researchers argue they are, but that their self-awareness is rooted in scent, not sight. To address this, scientists have developed olfactory mirror tests. In these experiments, dogs are presented with urine samples from themselves and other dogs. Studies have shown that dogs spend significantly less time sniffing their own scent compared to others’, suggesting a form of self-recognition—they already know what they smell like. While this isn’t as visually dramatic as the mark test, it points to a canine form of self-awareness.

Other Notable Failures

Many other intelligent species have not passed the mirror test, including:

- Pigs: Despite being highly intelligent and social, pigs do not show signs of MSR.

- Parrots: Species like the African Grey Parrot exhibit remarkable cognitive abilities, including advanced language use, but have not passed the mark test.

- Octopuses: Do octopuses pass the mirror test? Despite their alien-like intelligence and complex problem-solving skills, they do not seem to recognize their reflections. This may be because their visual system and body image are so radically different from vertebrates.

The Mirror Test Controversy in Animal Studies: Limitations and Criticisms

Despite its widespread use, the mirror test is far from a perfect measure of self-awareness, and it is steeped in controversy. Critics point out several significant limitations.

1. A Strong Visual Bias

The most prominent criticism is the test’s reliance on vision. It inherently favors species for which vision is a primary sense. Why should an animal that relies on scent (like a dog), echolocation, or electrical fields be judged by a visual standard? Failing the test may not indicate a lack of self-awareness, but simply that the test is inappropriate for that species’ sensory world.

2. Interpretation of Failure

A “fail” is not a definitive result. An animal might fail for numerous reasons unrelated to its cognitive abilities:

- Poor Vision: The animal may simply not be able to see the mark clearly.

- Lack of Motivation: The animal might see the mark but not be motivated to touch it. A small dot may not be interesting or concerning enough to warrant a reaction.

- Physical Inability: The animal might not have the physical dexterity to touch the marked spot.

- Social and Behavioral Constraints: As seen with gorillas, a species’ natural social behavior (like avoiding eye contact) can interfere with the test.

3. Self-Recognition vs. Social Behaviour in Front of Mirrors

Some researchers argue that the behaviors seen in the mirror test are not evidence of abstract self-awareness but rather a sophisticated form of learned social behavior. The animal may learn that the image in the mirror perfectly mimics its own actions and use that information to investigate a sensation on its body, without necessarily forming a concept of “self.” It could be a clever association rather than true introspection.

4. The Binary Pass/Fail Model

The mirror test provides a simple pass/fail outcome, but cognition is rarely so black and white. Many researchers believe self-awareness in animals exists on a spectrum. An animal might possess some elements of self-awareness without having the full package required to pass the MSR test. The test doesn’t allow for this nuance, branding species as either “self-aware” or not based on a single, narrow criterion.

Alternatives to the Mirror Test for Non-Visual Species

Given the limitations of the mirror test, scientists are actively developing alternatives to the mirror test for non-visual species to explore animal cognition and self-awareness across a wider range of species. These alternative methods are tailored to the unique sensory and behavioral characteristics of the animals being studied.

- The Olfactory Mirror Test (Sniff Test): As mentioned with dogs, this method leverages scent. By presenting an animal with its own scent alongside the scents of others, researchers can observe if the animal shows differential treatment. Reduced investigation time for its own scent is interpreted as a sign of recognition. This is a powerful tool for studying self-awareness in animals, especially canids and rodents.

- Body Awareness Tests: These tests assess whether an animal understands its body’s position in space and how it can act as an obstacle. In one study, elephants were tasked with stepping on a mat to pick up an object attached to it. They quickly realized they had to step off the mat to complete the task, demonstrating an understanding of their body’s role in the physical problem. Similar tests are being developed for dogs and other animals.

- Episodic Memory Research: Episodic memory—the ability to recall specific personal events from the past (the “what, where, and when”)—is considered closely linked to self-awareness. Studies with scrub jays have shown they can remember where they cached certain foods and when they did it, preferentially retrieving perishable items first. This suggests a sense of personal past, a key component of selfhood.

- Metacognition Studies: Metacognition, or “thinking about thinking,” is another advanced cognitive trait linked to self-awareness. Researchers test this by giving animals an option to “opt out” of a difficult cognitive test, usually for a smaller but guaranteed reward. Animals that consistently opt out of trials they are likely to fail are thought to possess some awareness of their own knowledge state. Such abilities have been demonstrated in primates and dolphins.

The Broader Implications: Animal Cognition, Self-Awareness, and Ethics

The quest to understand self-awareness in animals is not merely an academic exercise. The findings have profound and far-reaching ethical implications. If an animal is self-aware, it possesses an inner world. It is not just a biological machine reacting to stimuli; it is a subject experiencing its own life.

This recognition fundamentally changes our moral obligations. A self-aware being has a sense of its own existence, a personal stake in its own life and well-being. The capacity for suffering in such a being is likely deeper and more complex. This challenges the ethical basis for practices like factory farming, animal testing, and keeping highly intelligent, socially complex animals like orcas and elephants in captivity for entertainment. If these animals have a sense of self, then confining them to small, unnatural enclosures may inflict not just physical but deep psychological harm.

This research into animal cognition compels us to treat animals with greater empathy and respect. It argues for the importance of environmental enrichment, protecting social structures, and considering the psychological welfare of every animal under human care.

Conclusion: The Mirror Test and the Future of Animal Consciousness Research

The mirror test, for all its flaws and controversies, remains a pivotal experiment in the study of animal minds. It cracked open the door to the possibility of non-human self-awareness and inspired half a century of research into the rich inner lives of animals. While only an exclusive club of species has passed, their success demonstrates that the cognitive abilities we once thought were uniquely human can arise in vastly different brains and environments.

The failures and limitations of the test have been just as instructive, pushing science toward more creative and inclusive methods for assessing consciousness. The journey is shifting from asking “Do animals recognize themselves in a mirror?” to “How do different animals experience their own existence?”

As we continue to explore the depths of animal cognition, we move closer to understanding one of life’s greatest mysteries: the nature of consciousness itself. This journey promises not only to reveal more about the animals with whom we share our planet but also to teach us more about ourselves and our place in the intricate web of life.